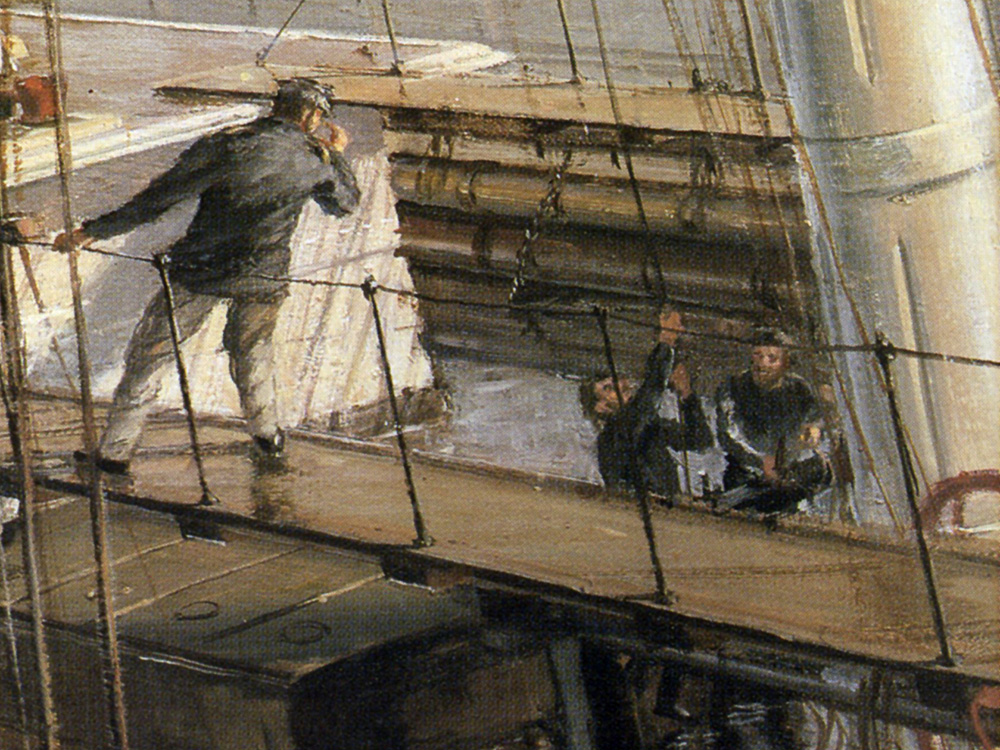

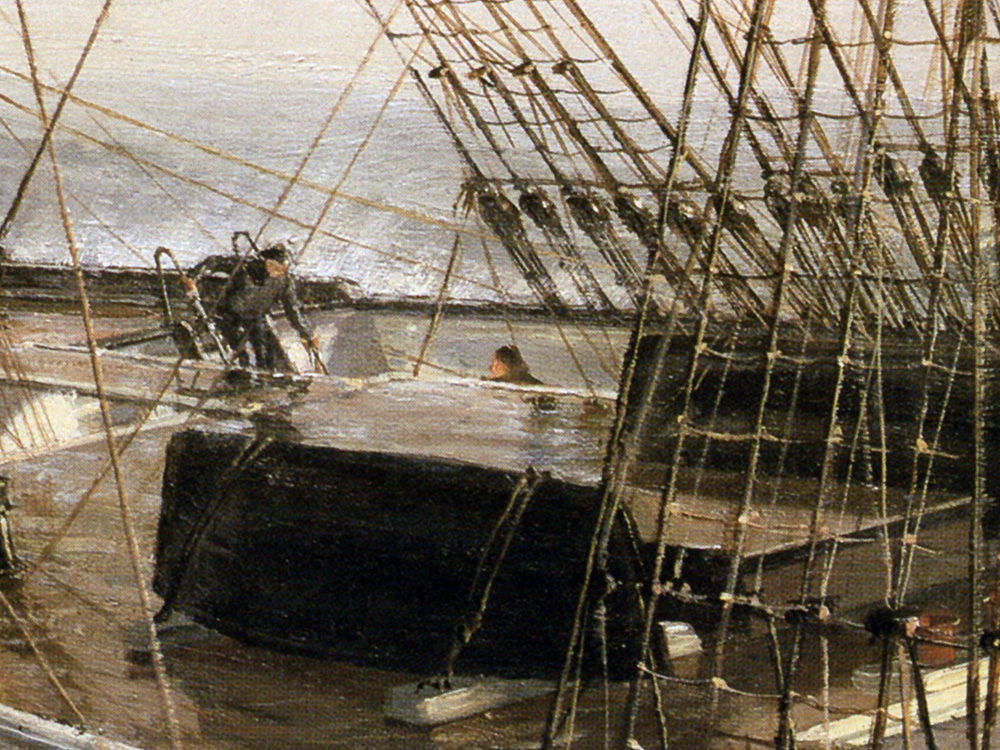

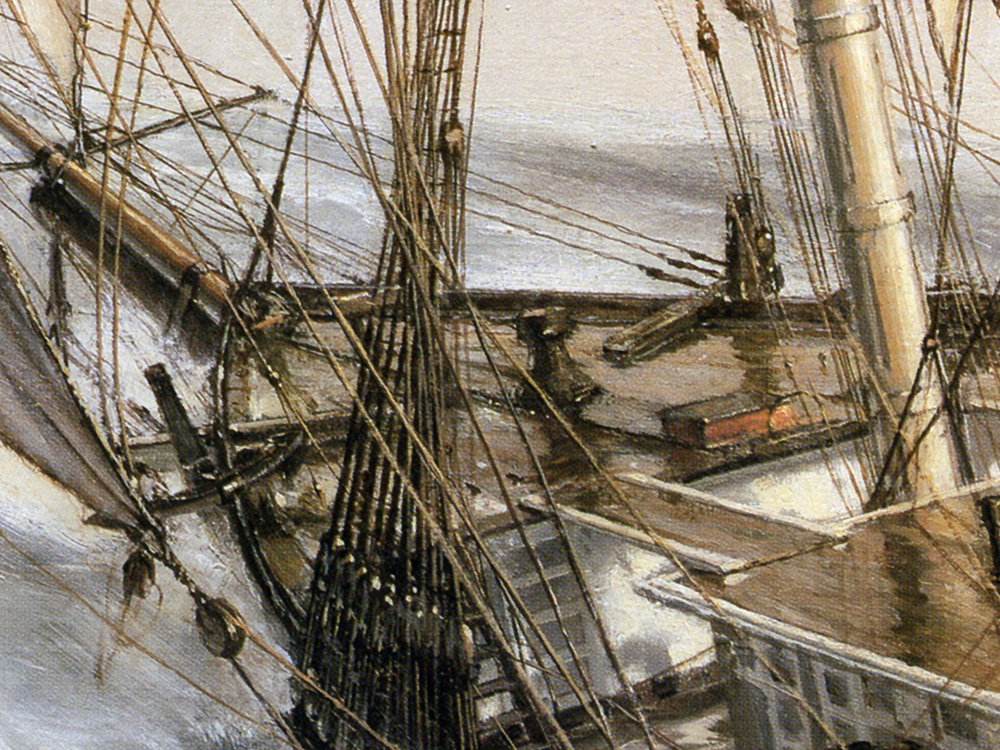

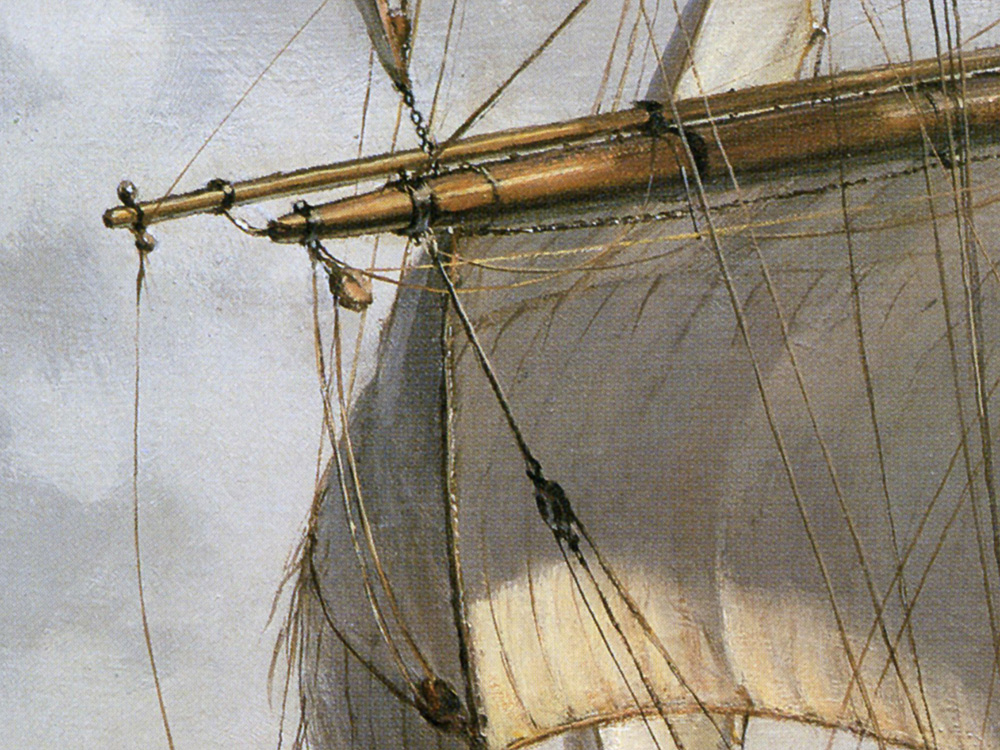

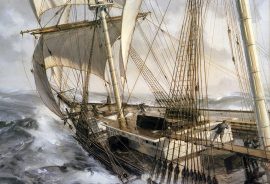

The “Lightning” Rounding Cape Horn

$850.00

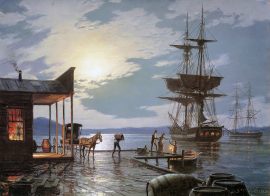

James Baines of Liverpool, ship-owner and naval architect, had raised enough local capital to start his Black Ball Line, which was not associated with the American packet line of the same name. Even though he was a young man without long years of practical shipping experience, Baines predicted the burgeoning Australian trade with accuracy.

Figuring that the tea clippers, mostly under a thousand tons, were not big enough for a healthy Down Under trade, Baines ordered the first of his large greyhounds from North American yards, beginning with the Marco Polo, built in New Brunswick, Canada. When the news reached England in 1851 that gold had been discovered in Australia, Baines was ready to capitalize on the situation. He felt that Donald McKay of East Boston was the only one who could build extreme clippers combining capacity with speed.

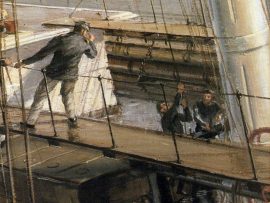

Baines knew of McKay's thirst for speed. The East Boston designer-builder, if given a free hand, would do anything to capture sailing records. The hand and the contract came from Baines. McKay quickly laid down four hulls for the account of the Englishman. One ship left the stocks in sixty days. The Lightning, the James Baines, the Donald McKay, and the Champion of the Seas were rapidly delivered to Baines in Liverpool to start their Australian runs.

The Lightning could handle about three hundred immigrant passengers. Most of these were impoverished Scots and Irish folk who boarded the Baines Vessels to find a new life in Australia. The Lightning's outward-bound passage took her south around the Cape of Good Hope with supplies and people, and when homeward bound from Melbourne, she sailed before the prevailing westerlies to the Horn and then up through the roaring forties and trade winds to Liverpool with wool and gold dust.

By 1860 Baines was operating eighty-six ships in his Black Ball Line, employing some three hundred officers and three thousand seamen. There were man who offered to buy his fleet, but Baines refused, and like some others continued to feel that he would always win with large sail-driven vessels manned by cheap crews. But Baines was not listening to the steam whistles. The coal burners were making serious inroads on windship trade worldwide. Around 1870, however, he was forced to give up. The “steam kettles” had won.

In stock

| Weight | 6.00 lbs |

|---|---|

| Catalog: | Stobart-169 |

| Artist: | John Stobart |

| Dimensions: | 19" x 29" |

| Image Size: | 30 1/4" x 23" |

| Edition: | 750 |