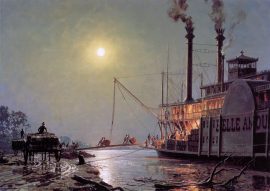

St. Louis: Laclede’s Landing c. 1885

$700.00

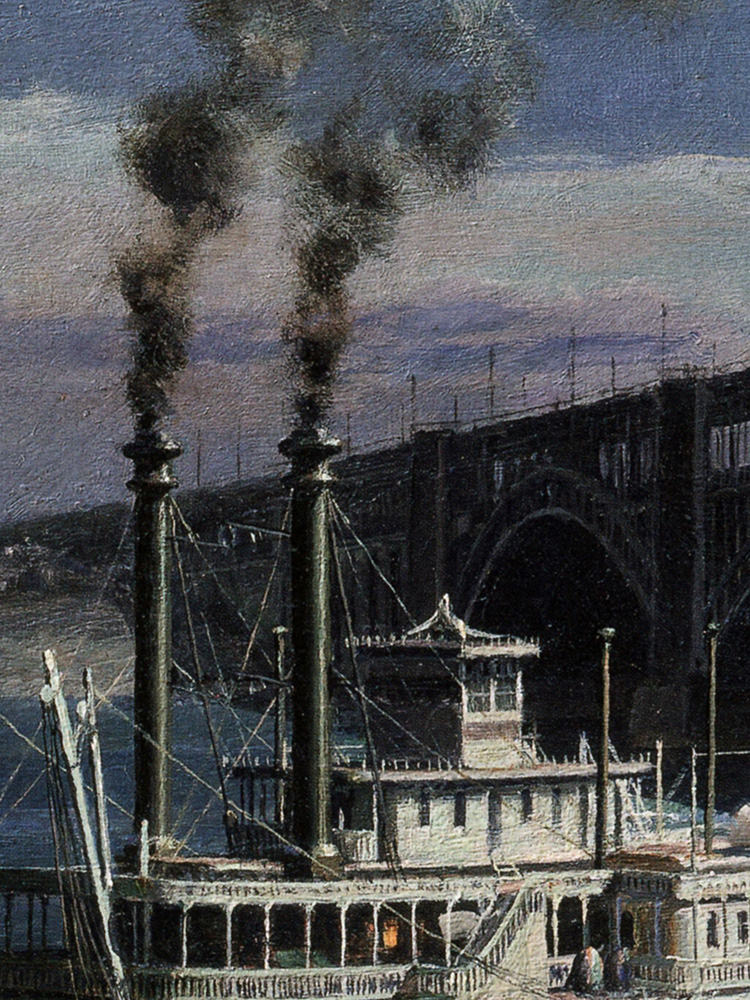

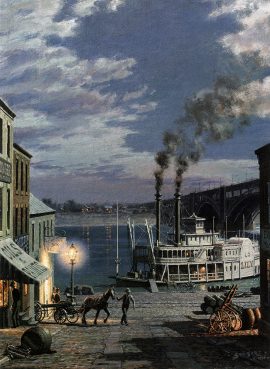

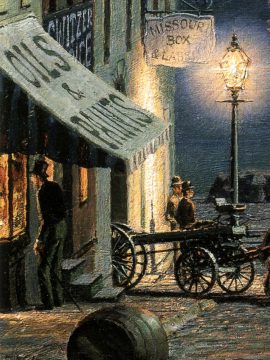

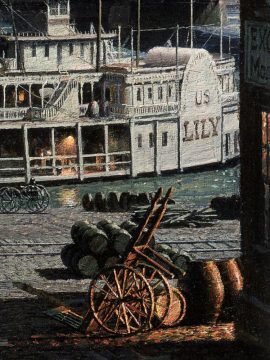

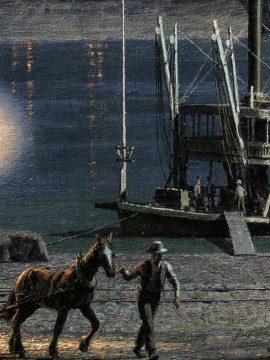

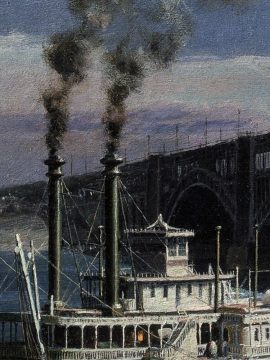

In this scene of St. Louis’s riverfront we are placed near the foot of Lucas Street. The unusual vertical format of this painting emphasizes the effect of looking down an enclosed thoroughfare to its opening, creating a sense of curiosity about the vistas we will experience when we get to the river’s edge. The area in front of us is known as Laclede’s Landing, initially a plat extending nineteen blocks along the levee and three blocks deep, with streets thirty-two feet wide. The landing is the only segment remaining of the original French village, which grew up around the trading post established in 1763 by Pierre Laclede Liguests and Auguste Chouteau. The lighthouse tender “Lily” is picking up supplies at the landing. Though the “Lily” was also featured in the painting CINCINNATI: The Levee at Daybreak, ca. 1884 on September 20th of that year she received extensive damage from a fire. She was completely rebuilt, and was given the Texas deck shown in this view of her one year later.

Traversing the river behind the ship, and just one block south of Lucas Street, is the Eads Bridge, built in 1874 by the self-trained engineer James B. Eads. This particular bridge is an epitome of the profo0und influence, often not easily realized by today’s population, that such bridges had on the nation’s development.Though there had been two bridges that crossed the Mississippi River earlier, both had given way to the strength of the river’s swift current, treacherous and capricious at best during high water. Whereas today the river’s power often takes even local citizens by surprise, those who lived in its vicinity during the time of this scene knew only too well her danger and unpredictability. Eads was well acquainted with the river’s flow, and he designed the mammoth steel-arch structure of three spans that rest on stone pillars sent down to bed rock far below the bottom of the river. The bridge today is still able to withstand the river’s moods.

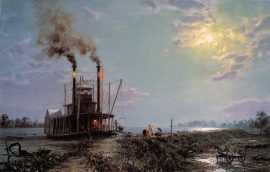

The technological advancements such as the Eads Bridge characterize the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Their inclusion in Stobart’s paintings returns a degree of respect and admiration they deserve but often are denied in today’s world where massive thoroughfares, expressways, and gentrified riverfront areas conceal their historical integrity. Stobart’s paintings taken as a whole also re-create the connective tissue of this bygone era, returning a degree of admiration to the intricate web of waterways that comprised the nation’s commercial trade. When the “Lily” appears in a scene of Louisville and St. Louis, or the “Kate Adams” in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, we start to read these paintings as small vignettes of a larger organism-of a larger topic. In moving from one painting to another we travel, just as would one of these steamboats’ passengers, from one inland port stop to another, experiencing the growth in communication that the steamboat brought to the inland commercial cities. We re-live, in essence, not just the experience of the scene before us, but even the experience of the nation’s heartland a century earlier.

| Weight | 6.00 lbs |

|---|---|

| Catalog: | Stobart-161 |

| Artist: | John Stobart |

| Dimensions: | 15 3/4" x 12" |

| Edition: | 350 |