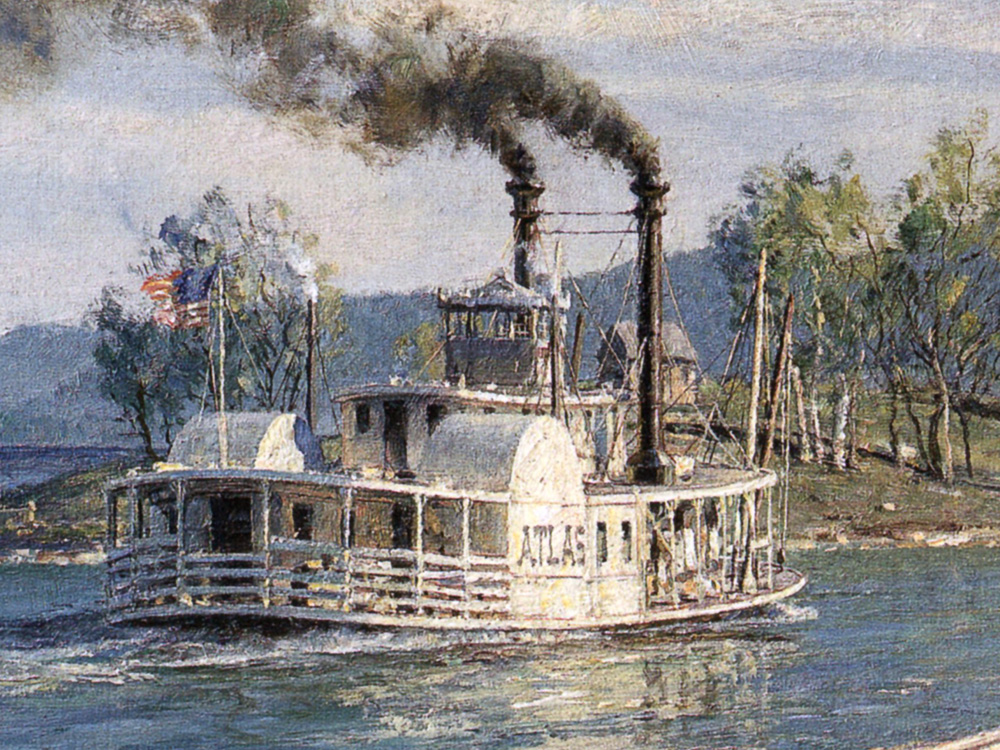

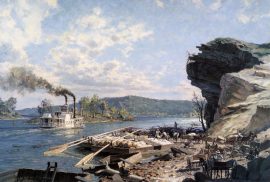

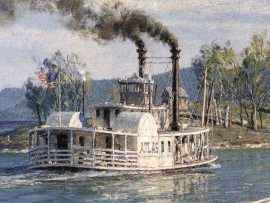

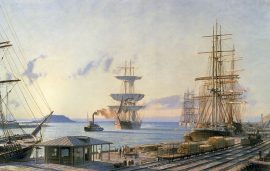

Chattanooga: Ross’s Landing Flatboats on the Tennessee River in 1848

$600.00

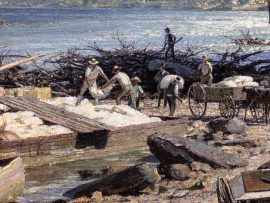

The location of this painting was named after the chief of the Cherokee Indians, John Ross. It is an area of great natural beauty, varying topography and major historical significance. The lowly flat- boat, conceived on the principle of the bottom of a duck, with very shallow draught, preceded the steamboat, yet was still in regular use for many years after steam had become widespread on America’s river network.

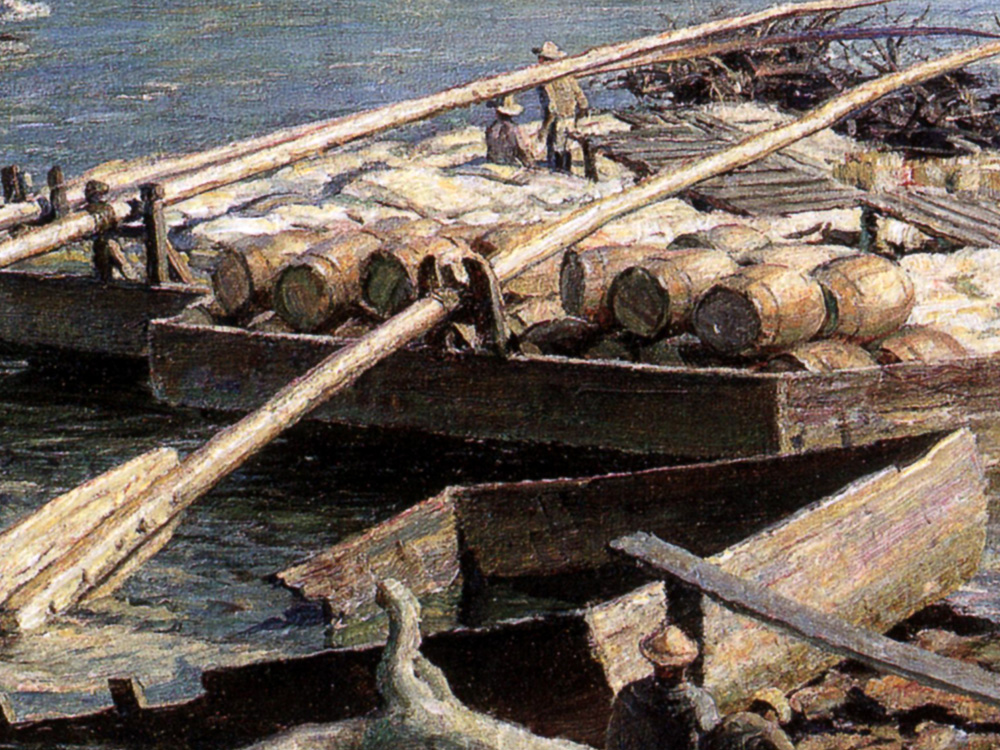

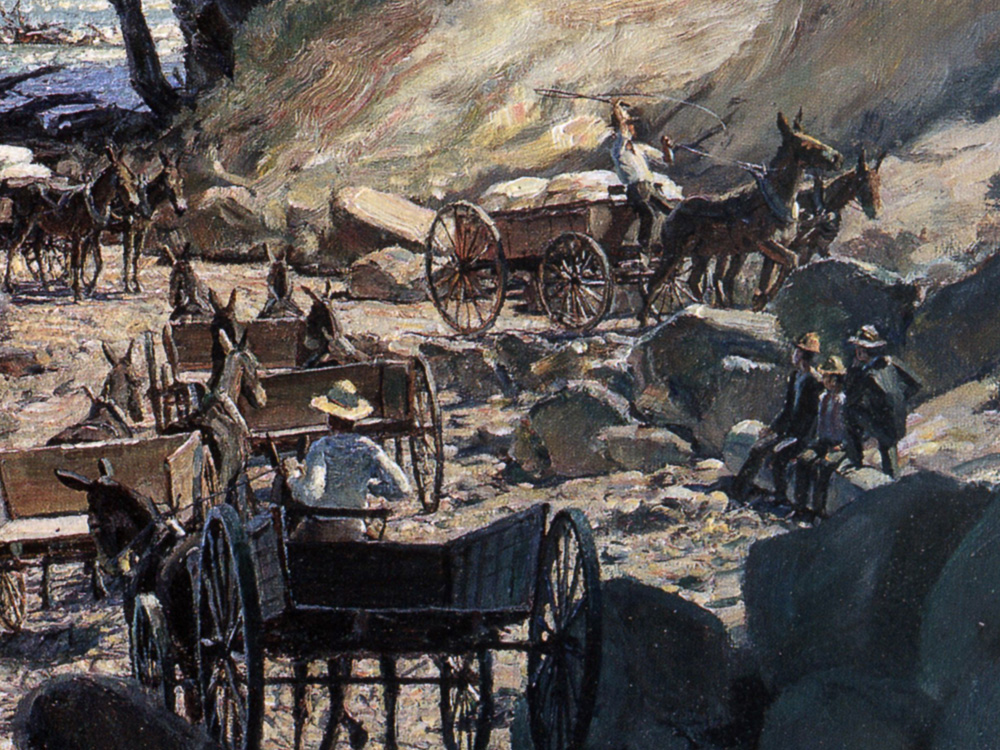

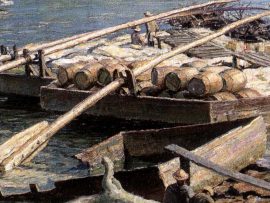

Flatboats had no motive power and were built to simply drift downstream with the help of sweeps, long oars that crew members would manhandle in order to avoid navigational hazards. The concept had a double purpose; firstly to carry freight long distances and secondly, to be broken up and sold at the end of the voyage for local construction projects. The crew would then be forced to walk home.

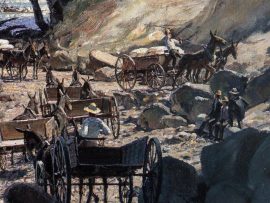

The Tennessee River flows a total of 650 miles before running into the Ohio River and Paducah, Kentucky. Below Chattanooga there were two major restrictions to navigation. These were the Muscle Shoals in Northern Alabama and, just ten miles below Chattanooga, a narrow gorge through the mountains called The Suck, also known as the Valley of the Whirlpool Rapids. These areas placed such limitations on steamboat traffic that the practice developed of “warping”or pulling boats upstream against fast currents with lines attached to windlasses on the riverbank.

The craft in this view would have been built on the riverbanks of East Tennessee and loaded with produce such as corn, wheat, potatoes, preserved meat in barrels, whiskey and sometimes even coal. At certain times of the year flatboats could drift over the navigational hazards all the way to New Orleans where markets would be larger and readier. The walk back home, however, could then take several weeks via a trail known as the Natchez Trace.

With the advent of the Tennessee Valley Authority, dams were constructed and locks installed both above and below Chattanooga making navigation more feasible. This heralded an era of new geography quite different from the “old river” of Harry Fenn’s etchings. Much of this terrain is now under water.

| Weight | 6.00 lbs |

|---|---|

| Catalog: | Stobart-027 |

| Artist: | John Stobart |

| Dimensions: | 19 1/2" x 29" |

| Edition: | 950 |